Seminar Presentation

A quick disclaimer before we really get into the text. I’m going to avoid focusing on writing style, because it’s there that I took the most issue, primarily in the first six or so pages. But I have to say a little to begin with, just to get it out of my system: Some of the self-indulgent, artist-elite vibes in the opening sections did not feel off to a good start. It didn’t last long, but it put me off the work immediately. For instance: “The skin of this parent-object is then split open, destroyed as it gives form to its new (child) object (the mother’s body is torn to pieces).” The entire point of metaphor is that it is an elegant stand-in for your larger idea, thus saving you from spelling it out entirely. While the addition of myriad parentheticals to a piece may make it seem hip and clever to the writer, it screams of indecisiveness to me.

Now, there’s a lot of good in this text not much further on, and work focused on people who are in-the-know on contemporary art is naturally not necessarily without value. My feelings on this may be entirely personal preference--I understand appreciation for exploratory musings on the whys and wonders of a piece. For me, I’d prefer to simply ask the artist their intention and be somewhat done with it. Its impact beyond that will be self-evident in the way it moves the average person who views it to further conversation (as evidenced later in the text), not in the masturbatory tete-a-tetes of the art world. For instance, the assertion that, “The child is deemed vulnerable in that he or she is dependent on the house as shelter for survival,” completely disregards the fact that we are all dependent on our homes, and that while we here wax poetic about artwork there are adults without homes suffering, sometimes dying, from that very lack. I appreciate the many excellent examples of other works she brings in throughout the text, but it seems to me that conversation about the meaning of art and the feelings associated with the problems it calls up into the collective consciousness without recommending a way to positively combat those problems and ideas is a conversation without substance, hot air without a balloon--you’re not going anywhere. But, I digress.

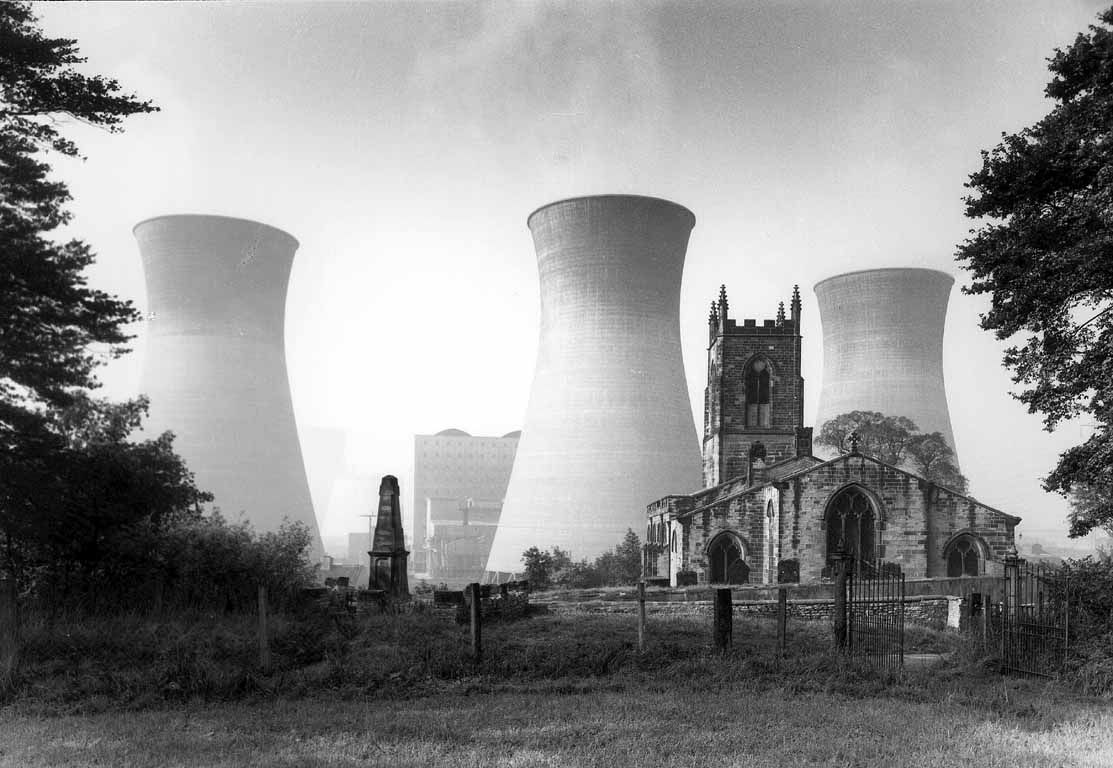

I’ll start off by showing you some of the excellent photographs that John Davies, in partnership with the artist Rachel Whiteread, took throughout the process of making and destroying House. It’s a little difficult to discuss such a profound and difficult work without first getting a sense of scale.

One can plainly see why Ashton mentions the “caresses and attacks of passers-by.” A work like this would command a great deal of attention from people of all classes, out of curiosity and respect for the magnitude of the creation. A prevailing trope in this treatise is tying the technique of casting to processes, both emotional and physical, mentioned throughout. The skin we wear, photography, our psychological “skins” all receive this treatment. As someone who has been lucky enough to work in shops, on houses, and overall in more “mundane” applications of art and artisanship, this rang true with me. It’s not only the size, location, and skills involved in the making of House that render it so memorable to people, it’s also the vulnerability of a piece placed as such, out in the elements, available to the public. Ashton mentions the world of ‘Do Not Touch,’ a world which I largely appreciate for the preservation of objects for other people. However, that very world is what makes accessible work like this so valuable, so memorable, and so important and impactful.

I’ll admit that the author largely lost me in Symbol, Site and Structure. It wasn’t just that it failed to hold my attention due to content that doesn’t interest me, but also that I disagreed with a lot of the prescribed intention and consumption. Again, this is the work of an artist who is alive and still creating--I find this kind of forceful language on “this is what the art means” without the simple, humble addition of “this is what this art means to me” to be off-putting. Yet, Ashton is clearly a well-read and -referenced professional, and some of the paths she goes down in this section are fascinating. All of the writers and artists throughout are extremely worth a look, from Bachelard, to Barthes, to Bourgeois (I’m getting the feeling there’s something about B’s here), and beyond throughout the piece, she’s given us a ton of research to do on wonderful bits of contemporary art and thought. This includes the work of sociologists Sarah Holloway and Gill Valentine in a much-appreciated inclusion of the sciences. The points extrapolated from that inclusion feel a bit broad at this point, but it’s still clearly the work of a strong researcher.

This does heat up a bit in the offerings of Don Slater on women and children being “restricted in belief and practice to the private world of the family which is subordinate to and ruled (through the male breadwinner) by the public sphere.” I don’t know how much these directly relate to the piece, but it is a fascinating point to bring into play. The Victorian stylings of the structure itself must call into mind that “cloying sentimentality” mentioned here. Ashton ties this all together very well with Simon Watney’s Ordinary Boys, but I was slightly troubled with the lack of a direct challenge to the Victorian ideal of sexuality as a negative, or as a threat to children. It may be that the subtlety of the argument was lost on me, but since I come from America, where many of the Puritanical and Victorian ideals still hold horrible sway on our ideas of sexuality and gender, a little more directness would be appreciated.

In Photography and Scultpure we have (to me) the beginning of more interesting arguments for the remainder, starting off with questions on the relationship between a short-lived sculpture and the photographs not only bearing witness to it, but becoming valuable artwork in their own right. This is followed directly by History of a House: An East End Sculpture wherein we get to the effects a profound work like this have on its public environment. As ever, when polarized political groups are presented with something to be used, they will use it with vigor. The writer gets deep into the theories on house, home, and the psyche, citing some fantastic researchers here, expertly bringing Doreen Massey’s writing on the ‘politics of location’ into play. This is where the text has some real teeth: in exploring the very real and very difficult realities that House was constructed in. Ashton’s clever discussion on the different definitions of “nostalgia” and our memories allude to one of the objects House most looked like to me upon first viewing: a gravestone.

Wrestling with the ideas of recording and “memory-work” is compelling, as ever, here. The notion of a cast interior as documentation is what was so enthralling about the piece to me in the first place, a recreation that is, but isn’t, what it sought to document. Like a 3D blueprint, it gives you a good idea of what was there without imparting any of the emotions, textures, or memories associated with that place. Davies’ images are then a further removal from the original copy, but no less valuable. As mentioned in the text, they add the theatrical setting indicative of “street photography,” but with some addition-by-subraction included--House is rendered lonely in these images, absent the populated and messy environment of 193 Grove Road. After getting a look at Davies’ other work, thanks to the well-written, concise history in the text, it makes sense why Whiteread would seek him out for this project. So much of his work mirrored the original piece, with “a deliberate framing of a space through classical detachment and an allusion to a mystical landscape.” Going further than just appreciating his work on this piece, Ashton brings into play a challenge to photography (and Whiteread’s casts) as evidence of personal history in general, by asking the question, “what was not photographed”?

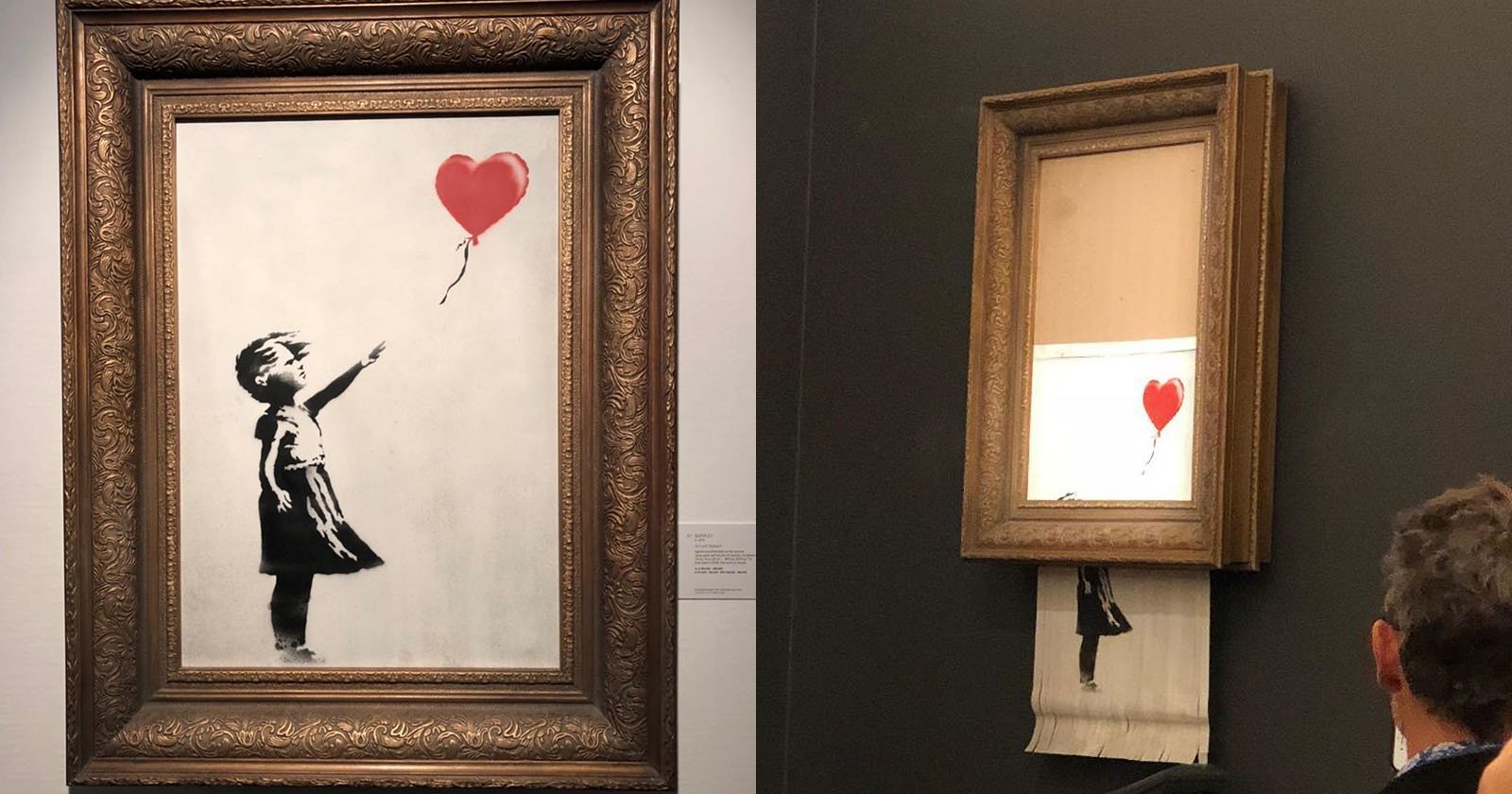

Ashton’s final argument on the destruction of house is accurate and eloquent, but for one aspect. She argues that, “The house is the ultimate consumerist object; a bourgeois myth which ‘empties reality’ and thus enables the domestic sphere and its ‘family’ to proceed as a ‘natural and eternal justification [...] A myth ripens because it spreads [...] A ceaseless flowing out, a haemorrhage’. The disruption of the house (via casting) and then its destruction is a violent stopper to such a haemorrhage.” I agree with the notion that it’s a stopper to “such a haemorrhage,” but for a slightly different reason. While real-estate has most certainly acted as a bourgeois ideal, often acting as a status symbol or bargaining chip for the wealthy, an item that acts less as a home and more as a simple asset, the trade of art has been close on its heels for some time now. It’s a lucky thing that House was demolished in the nineties and didn’t live to the Now, or we may be seeing its casts sold off for hundreds of thousands. In a world where art as a commodity has, according to Larry Fink (CEO of Blackrock), become a contemporary of real estate in New York, Vancouver, and London, perhaps it’s better to be a ghost.